Lee Kofman is an author, writing coach and speaker. Her latest work is a writing and reading guide, The Writer Laid Bare, which I’ve found incredibly valuable in my writing journey. Today, we discuss the challenges and benefits of its key principle: how to write honestly.

Thank you so much for spending time with me today. To set the scene, can you please share the blurb for The Writer Laid Bare?

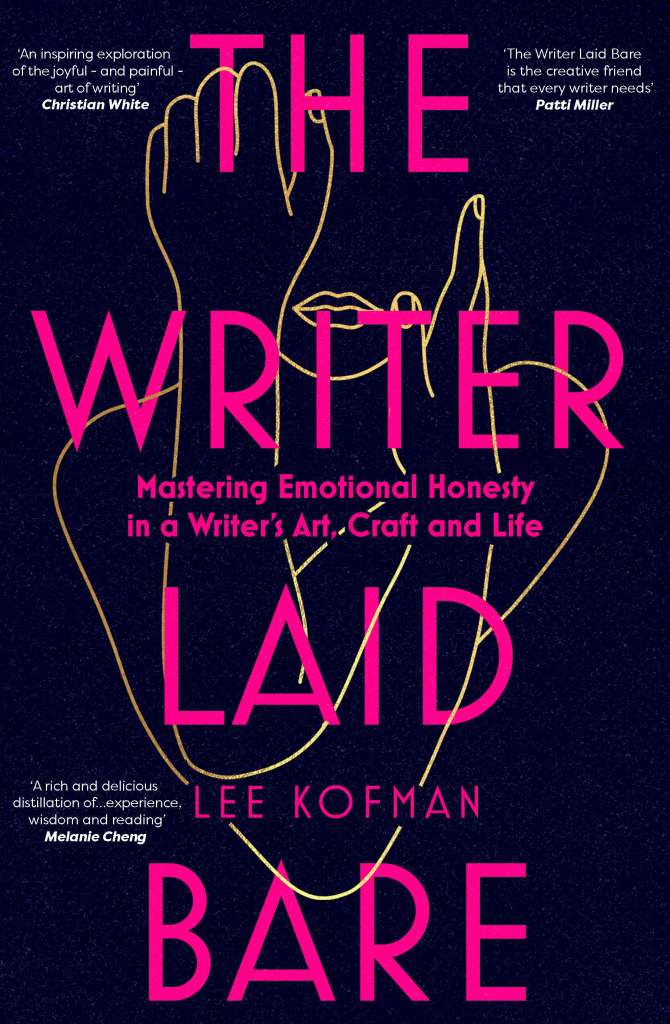

The Writer Laid Bare is a book for everyone who loves the craft of good writing. Be they a voracious reader wanting to know more or an emerging writer themselves, best-selling author and writing coach Lee Kofman has distilled her wisdom, insight and passion into this guide to writing and emotional honesty.

A combination of raw memoir and a professional writing toolkit, Lee examines her own life, rich in story and emotion to reveal how committing to a truthful writing practice helped her conquer writer’s block and develop her own authentic voice.

‘Show don’t tell’ has never been so compelling.

Inspired by her popular writing courses, Lee also offers practical advice on drafts, edits and how to achieve a life/writing balance. How combining her writing with motherhood led her to recognise that ‘the pram in the hall’ issue is real.

Plus the ultimate reading list of books you really should read, from Chekhov to Elena Ferrante and Helen Garner.

‘The Writer Laid Bare takes us on an intimate journey into the magical, and often challenging, terrain an author inhabits. Kofman courageously shares with the reader her own probing writerly journey of self-discovery.’ – Leah Kaminsky

I noticed in your bio that you have a PhD. What was it in and what was your thesis?

It wasn’t in creative writing. I am social worker by training and my PhD was a crossover between social work, sociology and psychology. It was about the impact of having non-facial scars on women.

One of my books, Imperfect, was informed by this study of women with scars, incorporating some of my research and the interviews I did, although it’s not academic. It’s my own story of having such scars, but it is also more than a memoir, it’s a creative nonfiction work with the components of investigative journalism and a cultural critique of what it’s like to have an ‘imperfect’ body in today’s world that admires perfection.

Intrinsic to how I work as a writer is that it’s always about real life. Even my fiction is inspired by real life.

The idea of honesty in writing memoir seems easy to grasp (if not to execute) but how does a writer apply honesty in fiction?

Emotional honesty comes down to writing about the world the way it is and the way we see it as writers, not the way we want it to be. Even for people who write in genres like historical fiction, where their work is completely removed from their own lives, eg. about crusaders, they still can base their characters on people they know in real life.

This helps writers not to turn their characters into case studies but think of them as individuals who contain darkness and light and contradictions.

And it’s impossible to write like this if we’re not honest about what we are like ourselves. We need to be self-aware too.

The level of self-reflection required to dig so deep sounds like a form of therapy. Do you think writers can benefit from therapy? Or do you see writing as a form of therapy?

I’m a former therapist myself and I think it really varies for each writer. Some need assistance from professionals to understand themselves and write better.

For me, I don’t make a lot of money from my writing, but I save a lot of money from it because I write about my wounds, not scars, which means things that have not healed yet. By the time I have finished the book, I usually resolve to some extent the issue I write about.

When I began Imperfect, my memoir about non-facial scares, for example, I still hadn’t told a lot of my good friends about my scars, which I got as a child. I spent all my energy meticulously hiding them, verbally as well as physically, but then there was my book for everyone to read. I outed myself.

I’m not healed completely, I still don’t like my scars, but they’re not as much in my consciousness now. Writing that book was a big part of that progression.

So, back to your question, it’s not a clear-cut answer. Therapy and writing are intertwined. I never write with a goal of healing. I don’t work like this. I write with curiosity out of desire and urgency. I’m just lucky it’s a side benefit for me, that writing sometimes helps me to cope with my problems.

Are there limits to what you will or won’t discuss in writing? There must be some private moments you want to keep just for yourself, and other things that readers probably don’t want or need to know. If so, how do you draw that line without sacrificing honesty?

Ideally, I’d like not to draw any lines. My favourite literary crush is Karl Ove Knausgaard because when you read him, you feel he doesn’t hold back at all. But I also wouldn’t want to be related to him.

For me, my line changes all the time. At the moment, I struggle around the fact that I want to write about motherhood. Both my kids have disabilities, so mine is not the average experience. There’s a lot to say there, and it’s urgent, but I struggle with writing about them because they will grow up and read it one day.

I’ve written a bit about my older child, who has autism and behavioural difficulties, but not to tell it all and I don’t know if I ever will. It’s hard.

In your acknowledgements, you say ‘One of the greatest misfortunes that can happen to a family is to have a writer born into it.’ You mention moods, deadlines, travels and anxieties. But do you also mean this issue of exposure? Can you protect the privacy of others when writing memoir?

I think about it as an ethical continuum, and we’re all different. Knausgaard sits at one end because not only does he share his own secrets, but he even shares secrets of other people who don’t know he knows their secrets. For example, he wrote about his mother-in-law being an alcoholic. She didn’t know that he knew, but he made it public. Other writers try to please everyone and check every draft and end up with a truthless inoffensive book.

On this continuum, I’d be closer to Knausgaard end, but not entirely. I give myself a license to reveal certain things about others even if they are not flattering as long as I am harder on myself than I am on them.

I wrote in an anthology, Split, which I edited, about a short difficult relationship I had before I came to Australia, when I was in Israel. He was a sociopath, and in the end, he kidnapped me. It took 20 years to write about it as I waited for a time when I could write more calmly and at a distance. This was both an artistic and an ethical decision because I needed emotional distance to see what happened more clearly. I could look at how my former boyfriend was parented terribly and held a terrible fear of abandonment. It was when I left the relationship that everything exploded.

Another thing I try to keep in mind, a rule for myself, is to tell my story but not their secrets. If something interesting and idiosyncratic can harm the reputation of a person I write about, and it is not directly related to my story, I hold back.

In a case like this, could you fictionalize that experience? Does fiction give you greater creative license?

I think it does. One partner I had used to gamble, and it gave me a close insight to the psychology of gambling. Now I understand it, so I might fictionalise it one day and have a character who gambles.

We’ve come full loop to talking about honesty in fiction again.

Yes. One of the common issues in manuscripts where writers write about what sits outside their experience is if they approach their characters as if they were a case study– read about gambling, find out about the average statistics – then the character doesn’t come to life.

The best thing to do is to think about the character as an individual we know. Let’s say I didn’t know a person who gambles, I can still base my character on a real person and meet a few gamblers and talk to them and combine them together into a specific person.

Often I combine two or three people in my head. The key is to always choose people who mean something to me. I call them comets. Comets – people who leave scorch marks on our lives – are creative gold. If someone moves me, positively or negatively, I will write about them. It helps to tap into our strong emotions.

This is essential to any creative writing of any genre. Even if I were to write historical fiction in the example we discussed earlier about a crusader, I would think about people who interest me in my life and shape the character around them.

In line with your first writing tenet – to write is to read – you list 100 books (mentioned and unmentioned in The Writer Laid Bare) as well as further reading on the art of writing (and reading). If you had to pick one recommendation as an example of emotional honesty, what would it be?

Chekhov’s short stories. Actually, I can talk about one extraordinary story, ‘Sleep’. It’s about a young peasant girl, who looks after a baby for another peasant family, but the baby never sleeps.

The girl can’t sleep and gets more and more worn out. By the end of the story, she kills the baby because she needs to sleep so badly.

The greatness of this story is that even though we are left with absolute horror, we also understand the girl. It’s not about excusing what she does, but about understanding.

It’s risky to write like this, but powerful writing is not about writing a clean life. Chekhov has a beautiful quote, I’m paraphrasing here, ‘A writer should be like a pharmacist [Chekhov was a doctor], to whom nothing on earth is unclean.’ It’s about being brave enough to look at life how it is, not as you want it to be.

As well as writing, you are a writing mentor and teacher. If an author wanted to work with you, what are their options?

I teach classes and I work as a mentor. I’m fortunate because I can afford to work only with those writers where I really love what they do. Normally I ask for a synopsis of about a page of what they are working on and a page of their writing related to their work. I’m pretty good at picking up enough from one page. Something in their voice needs to speak to me, some spark, I can’t explain it, but I’ll feel if I can connect.

Usually I’m booked out in advance, so if a writer is prepared to wait three to four months, I can fit them in.

I work in a way that saves money for writers, I never do pre-paid packages, or I don’t often do full manuscript assessments as I can read less, charge less and still offer the same structural advice. I can spot many structural issues just from an extract. I often give detailed feedback on extracts that they can apply to the rest of their work, so they don’t have to spend all that money.

What next?

I’m trying to write two books at the same time. They have been sitting with me for many years – a memoir and a novel. I can’t say more as I have a superstition about saying too much. I work on them in a tentative spirit, to see if either of them takes root.

Is there anything else you want to add?

Emotional honesty isn’t just what we put on the page, but it is also about our creative process and what our needs are. And about how, as writers, we live our lives. It’s hard to separate art from life, so we must interrogate ourselves about how much we are willing to sacrifice for our writing. How we live our lives impacts what we put on the page.

You can follow Lee on:

Website: leekofman.com.au

Facebook: Lee Kofman

Insta: @leekofman

Booksales link: The Writer Laid Bare

Next time: Christmas Book List 2024

Next interview: by Sophia Voukelatos, Kirsten Alexander on After the Fall.

One thought on “Lee Kofman on The Writer Laid Bare”