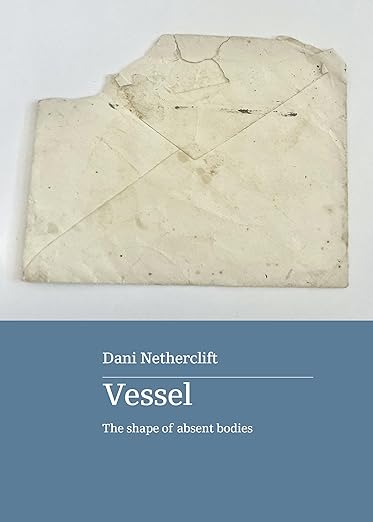

In her book, Vessel, The shape of absent bodies, Dani takes us on a transformative journey as she grapples with the drownings of her father and brother and finds solace through the process of writing. This lyric essay plays with fragments of memory, draws connections in history and with literature, and takes a deep dive into emotion.

Join me as Dr Dani, President of Mansfield Readers and Writers, explains her PhD, Vessel and the healing power of words.

Can you please share the blurb for Vessel, The shape of absent bodies?

Who would think to call Ophelia a corpse? She is but a woman emptied of herself.

In 1993, when she was 18 years old, Dani Netherclift witnessed the drowning deaths of her father and brother in an irrigation channel in North-East Victoria. Or, she saw her father and brother disappear beneath an opaque surface and never saw these loved ones again. But also, never stopped imagining the shape of this bodily loss. Not viewing the bodies grows into a form of ambiguous loss that makes the world dangerous, making people seem liable to suddenly vanishing.

What would it have been like to have seen them, after the fact? To have looked upon their bodies. To picture the emptied vessels of her father and brother is to reach toward a sense of closure; a form of magical thinking in which goodbye is made possible. Vessel pulls together a language of space and ruin, interleaving stories of what it means to lose the physical body of a person you love with a bricolage of literature, history and (vessel) translations, and the realisation that all bodies become in the end bodies of text, beautifully written palimpsests—elegies—inked on the skins of the dead.

Have you always been a writer? What led you to do a PhD in creative writing?

I always wanted to write and always wrote poetry (not necessarily good poetry) but at least I kept putting words on the page. I started two university degrees in writing in my twenties, but each time, I found that I wanted to get on with life rather than write essays, so I dropped out, which I think was a good thing, as I don’t think I was ready then to be the writer I am now.

In my 20s, I moved to Northern NSW and then returned to Melbourne and worked in wholesale clothing and jewellery. In my 30s, I moved between Melbourne, Sydney and Geelong for work and love, with behind-the-scenes jobs in the fashion and jewellery industry.

I didn’t write much except in my own journals until I had my son in 2012, when I started writing a blog. After I had my daughter two years later I began the Deakin University Bachelor of Arts in creative writing, two subjects at a time. I graduated with Honours after four years of online study.

Then I moved to the high country of Victoria and on to a PhD. I was really in love with the depth of research in postgraduate study. I have had over 30 poems, essays and reviews published in literary journals, and have won, been shortlisted or highly commended in various competitions over the last five years, so a longer work was a natural extension of what I had been writing.

What was your thesis topic?

The title of my thesis was The Elegiac Lyric Essay. The premise of a PhD is that you make a significant contribution to new knowledge. I invented or coined the term the elegiac lyric essay as a subgenre of lyric essay.

As the PhD was a creative arts model, I also needed to produce what’s called a creative artefact, in this case, a book of publishable standard.

Can you please define lyric essay?

Lyric essay isn’t a well-known genre in Australia, where we’re more likely to place it under the broad umbrella of creative nonfiction, but another book came out last week that I was excited about, Shapeshifting: First Nations Lyric Nonfiction, edited by Jeanine Leane and Ellen Van Neervan. A sentence in the introduction captured it perfectly. ‘Lyric nonfiction is unpredictable and derives meaning from the act of writing itself.’

Lyric essay is organic, and the themes emerge in the writing. One memory leads to another memory or thought; this is how it imitates the way memory works. The construction of the essay is like that of a mosaic, assembling these fragments of memory, quotations and thoughts together into something that works to create meaning.

And what is elegy?

Poetic laments for and commemorations of the dead.

Can you explain a little more about the PhD and how you penned Vessel?

I conducted my PhD research on two aspects. The exegesis is the theory and scholarly aspects (what you would call the traditional thesis) and mine explored what elegy is and what lyric essay is and how they intersect and can naturally work together. The creative component of my work was about grief and bodies and how they have been represented in literature, history and culture.

It was practice-led research, which is to say that, via doing it, I was working out how one writes and ‘constructs’ or assembles a lyric essay. For Vessel, this involved piecing together some of the quotations and sources I’d studied about how we write about the dead, and the importance of the body in writing, and braiding and meditating on how it reflected on my personal experience.

Bodies are important, as can be seen throughout history when people didn’t have bodies to help them grieve, such as in 9/11, or the Holocaust. In the book, I looked at how other writers had dealt with this. I threaded that in a non-linear way, comparing in a brief series of interconnected fragments for instance how bodies from 9/11 are still being identified today via fragmented traces, with the story of my mother’s uncle who died on the second day he fought in PNG during WWII, his body buried beside the jungle track and never found. Recently, my mother was asked for a sample of DNA by an Australian university as they continue to identify fragments of the bodies of fallen Australian soldiers in PNG (this is a PhD project in fact). My great grandmother had a plaque affixed to her gravestone for my uncle, her son, which goes to show that bodies continue to matter as time passes.

After describing examples in real life and literature, I always had to circle back to the personal, intricately mosaicking those pieces into the larger whole of the book.

What made you choose Vessel as the lyric essay for your PhD?

Though it has been over 30 years, I hadn’t ever been able to write a proper account of what happened to my family until I discovered the form of the lyric essay in my undergraduate degree. Without the mandate of a classical narrative arc, I found this genre could ‘hold’ my experience of witnessing the accident and my journey of grief via writing in fragments that recalled events similarly to the ways memory itself works.

A natural arc evolved as I reached a place of peace by laying the textual bodies of my father and brother to rest. One incident that drove this resolution was when I was writing Vessel, I helped my mother move house. I went through my older brother’s possessions, which had been stored in a trunk and never opened, and I found diaries he had written when he first moved out of home from the tiny Mallee town we lived in then, to the city. Nobody ever knew he wrote them. They only followed a year and a half, but this body of text in one sense brought him back to life for me.

You can have a person’s words as well as the way you write about them and your memories. In the end, that body of writing is what you’re left with in place of a physical body, and that is something that you can view and work with. This is what I explored in the creative aspect of my PhD.

How did you enjoy the experience of writing Vessel as part of a PhD?

I was fortunate to write my book through a PhD because of the level of mentorship involved. This entails monthly meetings with a supervisor (conducted on zoom for me), and regularly sending work to them for feedback.

I started with the writer Briohny Doyle as my principal supervisor for the first year and a bit, then Briohny left Deakin for the University of Sydney and David McCooey took over as my supervisor. David had been the one to initially suggest the form of the lyric essay as a topic for my PhD, and as an outstanding writer of poetry, essay and critical reviews with an enormous amount of experience in these areas, he was a tremendous source of knowledge and as first reader of my work, gave invaluable regular feedback.

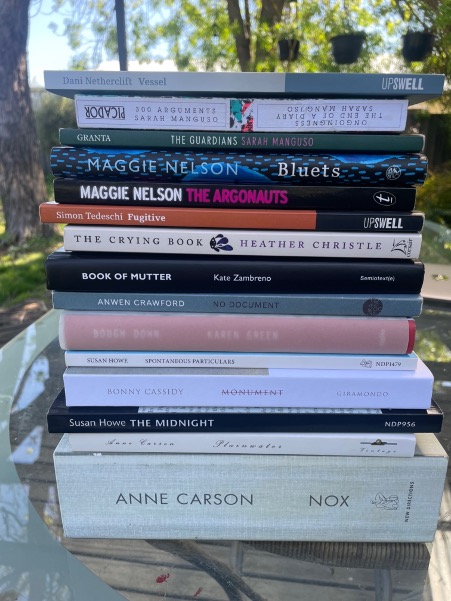

Were any specific books helpful to your journey?

Anne Carson’s Nox was a revelation to me. It’s a concertinaed stack of pages contained within a box and is a replica of a real-life scrapbook that Carson made to make sense of her troubled brother who had died after a long absence. This sent me down the path of wanting to write elegy that was also concerned with art, or the appearance of how the book looks on the inside. How Vessel appears on the page was critical to how I assembled the work, with pictures, scanned images of vintage envelopes to represent emptied vessels, white space and text presented in unconventional ways. The nonfiction writing of Maggie Nelson, Sarah Manguso, Susan Howe and others also informed my work.

Ultimately, what is the crux of Vessel?

Vessel explores unresolved loss from not viewing a body. How do you deal with assimilating death if you don’t see a body? Via the process of writing, and mosaicking it with the writing of others, I transform the bodies of my father and brother into bodies of text and enact a sense of closure. It sounds complex, and has a lot in it, but it all fits together and is easy to read.

You can follow Dr Dani on:

Website: https://dani.netherclift.com.au/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Sandhasnohome

Insta: https://www.instagram.com/dani_netherclift/

Twitter: https://x.com/daninetherclift

Booksales link: https://upswellpublishing.com/product/vessel

Next time: Lisa Darcy on Christmas Actually

2 thoughts on “Dani Netherclift on writing to resolve grief”