Timo works at the forefront of machine learning with experience in startups, Google, and now Snyk. In parallel, he wrote his debut novel, which showed him how hard it is to find a publisher.

Last year, I interviewed Timo about his newly published thriller novel, The Scaevola Conspiracy, which follows a couple of new graduates who join one of the biggest IT companies on the planet. We also touched on the AI app he was developing for the literary world called Quantifiction Iris. I promised to run a follow-up interview about this, so here it is.

To recap … with a foot in both the literary and AI worlds, Timo asked himself whether he could use his machine learning knowledge to figure out what makes a good book. Humans aren’t efficient at assessing submissions because of their subjectivity and how long it takes them to read. Iris can review a whole book and predict its sales potential in a few seconds.

The use of AI in the literary world has sparked much controversy, so with an expert in the house, let’s put our questions to him.

How can AI learn what will make a bestseller?

Just the same as humans would do it, by reading lots of books – both commercially successful ones and those that didn’t fare so well. Ones that rate well and those that don’t. Note the tool distinguishes between sales potential and estimated rating – quantity and quality if you will.

We fed our models with tons of texts from the internet and other sources and gave it what we’d call in human terms ‘experience’. That process is similar to how ChatGPT, Gemini or other models are trained to make them speak, but with one key difference. We used fiction texts and connected them to measurements indicating how these texts rated on Amazon, Wattpad, and other book sites. By telling our model what sells and what doesn’t, what rates well and what doesn’t a few million times over, it learns the differences in a completely objective way.

It was important for us to get the data distribution right. Say for example you train your model only on bestsellers, then it will predict 100% of all books to be bestsellers – it simply doesn’t know anything else. So we trained it with the same mix of books as exists in reality.

Do you have the rights to train the machine on existing books?

I wish I could answer this question with a clear yes or no, but the reality is nobody knows exactly since the courts of the world haven’t decided yet exactly what lawful ML training means. Quick legal detour: Authors retain the copyright of their work, but there are some ways around this. In the US, it’s called the fair use principle. For example, if you quote only a sentence of a short excerpt from a book, you’re not violating the author’s copyright since this is considered fair use. Over the years, courts have decided a few such exceptions, and for ML training the verdict is simply not in yet.

While many big companies trust courts to rule ML training to be fair use, we’ve adhered to two main principles to make sure we can ultimately answer this question with a resounding yes. First, the output of our model is numbers, not text. Hence, Iris can’t reproduce any of its training data, which is the main concern of copyright law. Second, our training data is based on a mix of manuscripts donated to us – for example, we offer Iris at reduced pricing to authors giving us the right to train on their work, and many have done that. We’ve used others that are likely to be ruled uncritical by the courts, such as works in online writing communities that have been explicitly published under permissible licenses, sample chapters of bestsellers publicly available on the internet, etc.

Ultimately, we want to serve authors and that includes respecting their intellectual property. But of course, we can’t serve them without any data, so we’re trying to strike the best compromise between training a high-quality model, and only using data that likely won’t raise any eyebrows in the writing community.

I understand that a machine can identify the technical elements of a book that make it successful, but how can it identify the magical ingredient the ‘je ne sais quoi’?

I don’t think machines will ever be able to capture these magical elements entirely – for that we’ll always need humans. If you look at millions of manuscripts, there’s a good chance you can capture a bunch of these ingredients, at least the ones that worked in the past. These patterns can be reproduced even by machines, or at least identified.

Of course, a truly new ‘je ne sais quoi’ won’t be found this way, that’s where our automated intelligence stops. But that’s not actually different from humans, we’re pretty biased in our assessments and also get things wrong. Many famous authors were rejected multiple times before an agent or publisher picked up on them – Stephen King for example.

Can you teach a machine emotions?

Maybe in the future, but right now I’d say machines aren’t capable of truly feeling or identifying emotions. What they can do is detect emotionally laden language, which in the end comes down to the words authors use to put their emotions on paper.

Large language models have made huge strides over the last few years to identify not just obvious word connotations but what’s written between the lines by analysing deeper and deeper levels of context. In other words, machines can’t feel emotions but understand how they are described. Of course, there might be scenarios where emotions are hidden or masked (multiple layers of irony for example), but in most cases, this is good enough to pick up on the main emotions like happiness, sadness, anger, etc.

How have publishers responded to this app?

It’s a very polarizing subject and we’re seeing two distinct camps. The traditionalists hear the words “artificial intelligence” and walk away before we can even explain what we actually do. Fear immediately takes over, and to a point that’s normal in such a mature industry. Then there are the open minds, who know AI is here to stay and embrace technological progress rather than block it.

We all know this isn’t an exact science, and some failures are expected. But that’s always the case with new technologies. In the early 1940s, IBM’s president famously said, “I think there is a world market for about five computers.” Eventually, AI will become as mainstream as computers have become over the last decades.

How can this tool help authors?

Authors can use Iris in a few ways. Our main score assesses the commercial viability of a manuscript, which helps authors gauge how ready it is to be pitched to publishers and agents. We measure this score over the progression of the manuscript, so authors can visually identify low points which they should focus on improving.

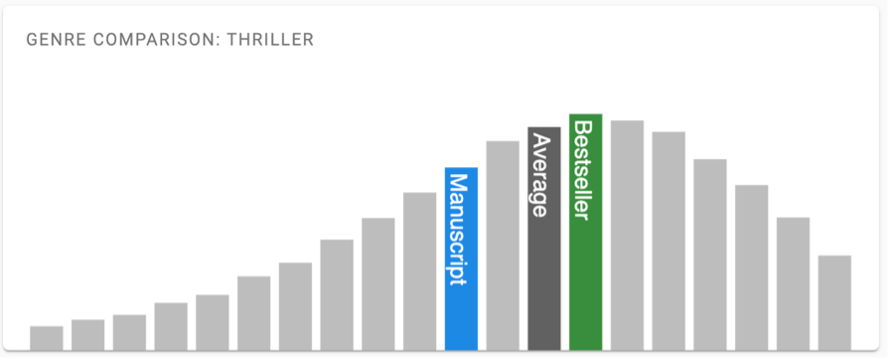

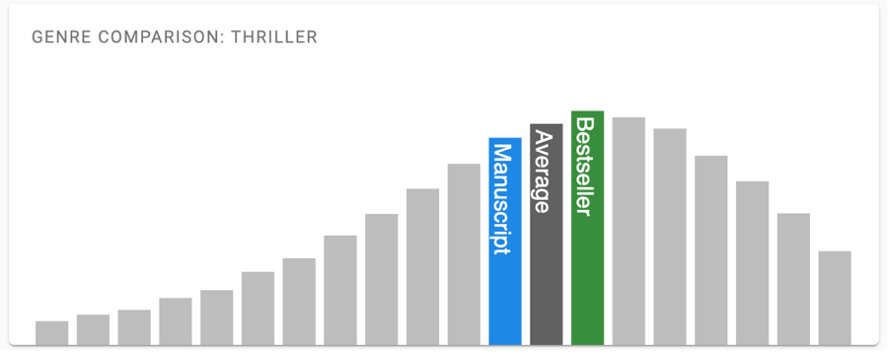

You can also dig deeper into certain metrics and see how your manuscript compares to works in the same genre. Take reading score for example, a standardized metric that measures how hard it is to read a certain text. Iris shows the average for your genre and what a normal range looks like. If your manuscript scores significantly differently, this could be a problem – you’re simply not delivering what readers expect.

Another example is pacing. We use a formula grounded in natural language research to measure how fast the story moves – think long vs. short sentences, and many vs. few adjectives. An author might already expect that a thriller should have faster pacing than a romance novel. We can visualize this, make it explicit, and see how your manuscript stacks up.

We’ve seen authors improve their overall score by up to 12 points. This means the system works: Find the low spots and potential issues, fix them, and ultimately rank better.

Will this tool replace editors?

No, definitely not. As with authors, we want to give editors a tool so they can be more efficient in their job. Iris identifies potential weak spots, deviations from genre norms and other potential problems. It can’t judge whether a potential problem is a real problem. Take pacing for example: even in the fastest-moving thriller, there will be moments of calm and slow exposition. Iris will find them and flag them to the editor. It’s the editor’s job to figure out whether or not this makes sense at this point in the story. If change is required, it’s the editor’s and the author’s job to figure out how it can be improved. That part requires creativity we certainly don’t want to replace by a machine.

To generalize: We don’t want to replace humans, whether they’re authors, editors, agents or publishers. We think writing is an art that can’t be comprehended by machines, at least not yet. But it’s also a highly subjective, slow and inefficient art that leads to the industry not reaching its full potential – ask any brilliant yet new author who struggles to understand whether their manuscript isn’t ready, or it’s simply being overlooked because nobody has time to read it. We want to provide tools to empower humans rather than to replace them, and ultimately help the industry to become a more effective version of itself.

Is Quantifiction complete, or are there still problems to resolve?

We’ve run a few trials, and they’re going well. But tools like this are never finished, they are always moving and progressing. It’s a work in progress.

One example we’ve stumbled across is where a place name is interchangeable with a person’s name, such as Houston. The machine might misrepresent a person as a place or vice versa. These issues can be fixed, it just takes time to identify and rectify them.

As a sample, can you show us how your novel, The Scaevola Conspiracy, scored before and after it was edited?

I ran 7 major drafts of The Scaevola Conspiracy through Iris, and from first to last, my manuscript’s overall score improved from 61 to 67. This doesn’t sound much, but there’s a clear upward trend from version to version that can be related to editing. On the other hand, I didn’t change the story or my characters, so I wouldn’t expect huge jumps. Also, Iris wasn’t fully developed when I wrote my manuscript.

One thing that clearly improved was genre fit, the metric that measures how closely the manuscript resembles its declared genre. By working with an experienced editor, The Scaevola Conspiracy became much more aligned with readers’ expectations. Another example is reading score, which measures how hard it is to read a certain text. In my first version, my manuscript was too far off the genre average and typical bestseller, and that improved with each consecutive version.

These differences look small, but they add up. I’ve heard from other authors that they were able to increase their overall score by up to 12 points. This can absolutely make the difference between a bestseller that gets picked up by a publisher and an ignored submission.

Where to from here?

If you’re interested to find out more, go to https://quantifiction.com/home. We’ve created a special discount for readers of this blog, check https://quantifiction.com/editor-trial to receive 30% when you try out Iris. And if you have any further questions, please add them in the comments.

You can follow Timo on:

Email: timo.boz@gmail.com

Book Website: https://www.scaevola-conspiracy.com/

LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/in/timobozsolik

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/timo.bozsolik

Twitter (X): https://x.com/TimoBozsolik

Booksales link: https://amzn.to/3OL47ye

Next time: Booklover Brooke Michie explains Bookstagram

3 thoughts on “Timo Bozsolik-Torres on Improving Manuscripts using AI”