Diane Clarke was born in South London and spent her childhood on the Sussex coast. She trained as a speech pathologist and worked in that field most of her career, continuing after she immigrated to Australia 27 years ago.

When she took three months off to find another job, she decided to dabble in writing, and now, her debut novel has been published, The Photograph, a family drama about a woman looking for her lost brother.

How did you transition from being a speech pathologist to becoming an author?

I began by taking a Queensland Writers Centre’s creative writing course and joining a writing critique group at my local library. They pointed me in the right direction and made me realize that a lifetime of business writing did not mean I could be a novelist. There’s a massive difference. I studied the art of storytelling through more courses, reading books about writing, analysing other novels, and putting words on the page.

Can you please share the blurb for The Photograph?

Caryl Hunter believes she lost her brother during the wartime evacuation of 1939. Her adoptive mother denies his existence and Caryl was too young to remember with certainty.

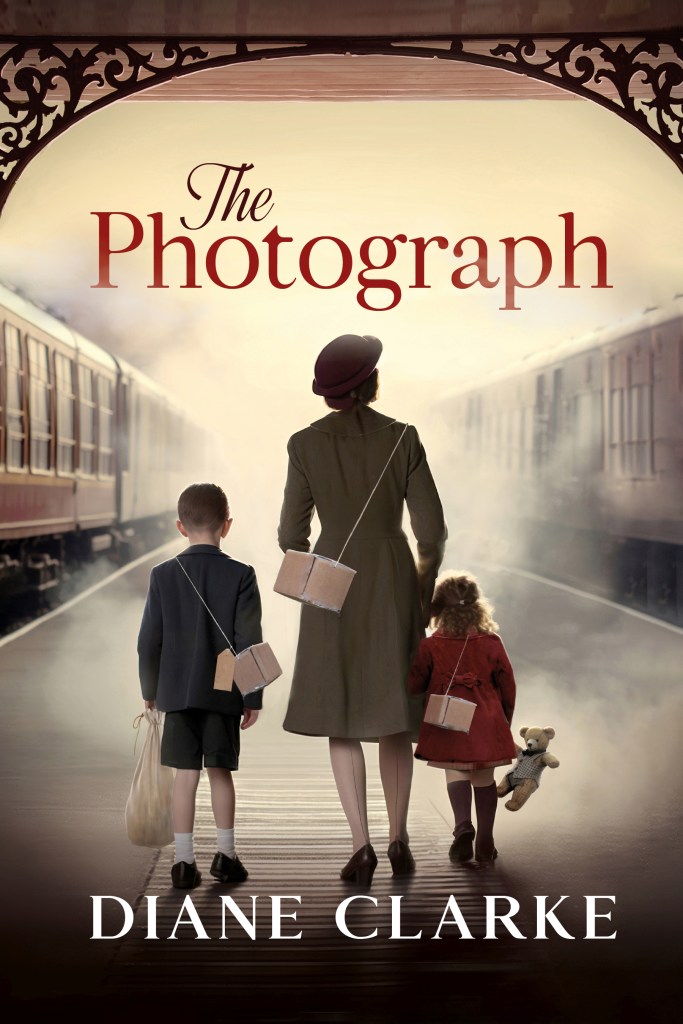

When she finds a black and white photograph of her family standing on a London station in the company of a mystery boy, her determination to find him reignites.

In 2020, Caryl’s daughter, Megan, takes up the search for her missing uncle. Confronted by her own secret, will she ignore it, or will she remember Caryl’s lifelong torment and avoid the mistakes of the past?

Caryl was a wartime evacuee. Can you tell us a bit about how this worked?

In the months leading up to WWII, when relationships with Germany were breaking down and people began to realise another war was a possibility, the British government knew the industrial cities would come under attack, so they devised a plan they called Operation Pied Piper. Families were encouraged to send their children to the country, away from London and the other big towns where bombing raids would take place.

On the first day of those evacuations, September 1, 1939, one and a half million children were put on buses and trains and sent to country towns and villages into the homes of complete strangers. The organization was mainly managed through schools, so teachers escorted their classes of children to these towns and made sure they each had a host family.

How did you explore this aspect of World War II in the novel?

My parents lived through the war years, so I grew up with war stories. The evacuation came up. I started looking at photos of that day in the national archives, shocked by the chaos, train platforms heaving with children, teachers and banners for schools. It struck me that there must have been a risk of children going missing or that older children with more resources and maturity, who weren’t happy with their host families, might run away. I couldn’t imagine such a scheme being undertaken today.

I need to give a caveat: despite the speed with which this operation was put into place, there are very few records of children going missing.

What else gave you inspiration for the story?

I saw a documentary about twin brothers, one of whom had lost his memory. They had a terrible family history that the twin with the memory chose not to tell the other. The discovery of a photograph not only cued the other brother that something odd must have gone on but forced his brother to divulge and face his own distressing past. I began thinking about family secrets, lies and photographs.

The Photograph is obviously very carefully researched. How did you go about exploring this part of history?

The evacuations are well documented in the Imperial War Museum and the National Archives. Website groups run by former evacuees encourage others to share their experiences of that time. I also found a Facebook group run by the British Evacuees Association, which provides information, connection and advocacy for former evacuees. In Part two, Megan works for an organisation based on this group.

Evacuees have been called the ‘forgotten victims of war’. There’s often recognition of war heroes like the RAF bomber pilots, the men of Dunkirk and various women’s groups but nobody really considered how traumatic this must have been for young children. They returned to their families at the end of the war when everyone was euphoric, so many didn’t talk about their experiences, especially anything negative, because they didn’t want to ruin the excitement. That’s what these societies hope to remedy. There’s now a beautiful statue commemorating the evacuees in Staffordshire, and evacuees attend the Armistice Day service at Whitehall every November.

Part Two of the novel centres on the time of Covid. Why did you choose this?

When I first developed the story, the second part wasn’t set in 2020 but advice from an editor encouraged me to think about moving it forward in time. When I considered bringing it into the Covid era, the parallels between this and the evacuations became clear, particularly to do with the trauma of separation from family.

At least modern-day families could phone or video call each other. In my novel, there’s a scene where Caryl and Megan’s family hold a Zoom meeting that wouldn’t have been available during the war. But even with these technological advances, we know from personal experience that lack of physical contact with family members was really difficult, reflecting what those children went through with far fewer means of keeping in touch.

The other parallel was the fear of death – everyone had that darkness during the war years, and Covid brought that out more recently.

The theme of family secrets crosses both parts of the novel. Can you please tell us a bit about that?

Part one focuses on Caryl, a 58-year-old who has lived her adult life believing she had a brother, but no one believes her. She hasn’t been able to find any records of him, so either he’s a figment of her imagination or someone is lying. The heartbreaking thing for her is that she never knew to trust her instincts until the photo appeared. It was the first piece of evidence that he might have been part of her family. Part one explores the repercussions of finding the photo.

In part two, Megan also has a secret, which a series of events forces her to confront. Her knowledge of Caryl’s lifelong torment is a clarion cry: could she be doing as much damage with this secret as Caryl has endured as a result of the lies told to her?

Another theme is restoration. How did you explore that?

A fantastic symbolism came with the discovery of the tiny black and white photo that had been stuffed in a teddy bear’s waistcoat for over 50 years. Caryl takes it to a photography studio to have it restored. You’ll need to read the story to find out whether other aspects of her life are restored, too.

Is there anything you’d like to share about your writing journey?

The biggest thing I came to learn is summed up in the quote, “A book emerges from the editing process.” In other words, we can’t expect our first draft to be the final. This story has evolved many times and for the better. I’ve learnt to “kill my darlings” as I now have the confidence to improve on a previous draft.

What can we expect to see next from Diane Clarke?

Another manuscript, The Bracelet, is near completion, then I’ll be looking for a publisher for that too. It doesn’t have a historical element, but the main character, Monica, is another woman having to jump hurdles to confirm her identity, understand her family and resolve issues from the past. She has plenty of secrets and lies to contend with, too.

You can follow Diane on:

Email: dianeclarke@iinet.net.au

Website: www.dianeclarkeauthor.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/DianeClarkeAuthor/

Insta: https://www.instagram.com/diane.clarke.author/

Booksales link: Amazon Australia

Next time: I explore Writing a Mystery: Crafting a Series

Next interview: Timo Bozsolik-Torres on Improving Manuscripts using AI

3 thoughts on “Diane Clarke on wartime evacuation and her novel, The Photograph”